This post is the second of a series of independently written technical briefings on the AWS S3 API and how it has become the de-facto standard for object stores. The series is commissioned by Cloudian Inc. For more information on Cloudian and the company’s HyperStore object storage technology, please visit their site at: http://www.cloudian.com/

Webinar: Join me to learn everything you need to know about the S3 API in a free webinar sponsored by Cloudian on 23rd March 2016 8am PDT, 3pm GMT

In the first post in this series on the S3 API, we looked at some general background information describing Amazon’s Simple Storage Service and the wealth of features it offers. In this post we dig deeper into the way in which security features are implemented in S3. The security aspects covered will include controlling access to data in S3; we’ll discuss the security characteristics of data at rest and in flight in another post.

Beginnings

When S3 was first introduced, there were only two main methods of accessing S3 content, either anonymously (in which case access was open to all) or using an authenticated request generated from access keys of the root AWS account owner. In September 2010, Amazon extended the security model to allow S3 resources to be controlled through the IAM feature – Identity and Access Management.

There are now five main access routes into S3 content; these are:

- Anonymous – resources can be made freely available for access by anyone, without the need to supply credentials.

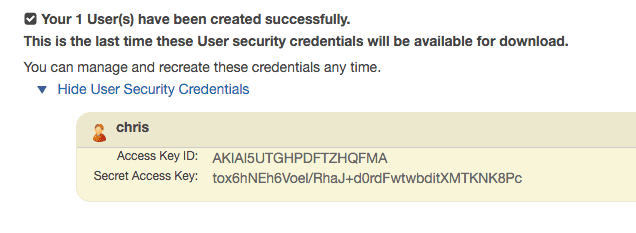

- Account Access Keys – using a signature generated from an account access ID/secret key pair.

- IAM User Access Keys – using a signature generated from an IAM user’s access ID/secret key pair.

- Temporary Credentials – using temporary credentials generated by an IAM user.

- Using Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) with one of the above methods.

AWS best practices recommend not using the root account credentials. The root account has by default access to every resource within the account, whereas IAM users by default have no access. AWS also recommends creating one or more IAM administrator users and using policies/roles to manage the granting of permissions to buckets and objects within them.

From the discussion so far, the terms and concepts of S3 security will be familiar to anyone who has worked with other directory services such as Microsoft’s Active Directory or generic LDAP. For those less familiar, this is a good time to put in place some definitions that will help us as we go deeper into detail.

Terminology

Permissions within S3 are granted to buckets (collections of data), objects (the actual content stored) or attributes of buckets and objects (like archiving policies). Permissions can be set through policies (either at the user or bucket level) or through specific Access Control Lists (ACLs). We’ll come back and discuss ACLs in a bit more detail in a moment, however in general Object ACLs provide more granular permissions over individual objects, whereas bucket and user policies provide more general grouping capabilities. Bucket policies have to be used when enabling permission from one S3 account to another.

IAM Users are individuals or services/applications that require access to S3 resources. Each IAM user has a userid/password that allows them to access features like the AWS console, however all S3 API requests are made using access keys generated by the user. These consist of an access ID and a secret key that are combined to make an access signature. The use of access keys in this way removes the need for the user to hard code userid/passwords into API requests that could be intercepted over the network.

IAM Users can be placed into groups, to allow group-level permissions to be assigned, however groups are not hierarchical and have a flat structure. Permissions can also be grouped into roles, that can then be assigned to users or groups. This idea will be familiar to Active Directory users where specific tasks (like data operator) can be attributed to a specific user without necessarily providing access to the actual content.

Policies provide a mechanism to assign permissions either to users or resources and the choice of which method to use is down to the user themselves.

Access Control Lists (ACLs) provide a mechanism for assigning permissions that was available before the introduction of IAM. Generally, AWS recommends using IAM policies however if ACLs are already in use, then there’s no need to stop using them. There are specific times when ACLs need to be used over IAM policies, such as applying permissions to individual objects within a bucket. There are also limits on the size of bucket policies, which may also mean using ACLs to get around this restriction.

Authorisation Requests

Non-anonymous access requests made to S3 are signed using the access keys of the user. The keys themselves are not directly used in an access request, instead a signature is generated using a combination of the keys and part of the data in the request (such as the parameters of a query).

Two versions of signing are currently supported, known as Signature Version 2 and Signature Version 4. Version 4 is supported in all AWS regions; version 2 is supported in AWS regions that were created before 30 January 2014 and is therefore the version for signing. The changes from version 2 to version 4 are focused around improving the security of requests and making it more difficult to spoof or steal credentials. For example, a signing key generated from the user’s secret key is used for signing messages rather than the secret key itself. Version 4 requests can also region specific and reference a regional rather than global endpoint.

Permissions as Code

Policy definitions are created using the Access Policy Language. This is a JSON-like coding structure that defines the policy and its attributes. Policy definitions don’t have to be created by coding – they can be generated using the AWS Management Console, the CLI, API or PowerShell. However, the ability to set permissions with code does reflect one interesting aspect of AWS, and that’s the ability to programmatically manage access to resources in S3. This makes it possible to extract definitions from one account, region or bucket and easily apply it to another. The ability to provide mobility to security definitions is a powerful tool and shouldn’t be underestimated when evaluating object storage vendors claiming to provide 100% S3 API compatibility.

Supporting External Users

What happens if the users that you want to provide access to aren’t based within AWS itself? This scenario is perfectly reasonable; imagine an object store used to retain medical records. From a compliance perspective it would be much more preferable to use some kind of external authorisation process that maps to an existing identity management system. S3 can enable that through temporary credentials that use Federation. The process allows integration with any OpenID or SAML 2.0 compatible authorisation process, such as Microsoft’s ADFS (Active Directory Federation Services). Another example could be providing access to data stored in AWS from a SharePoint environment.

Benefits of Maturity

So adding this all up, what benefits do we get from the way security has been developed in S3? Some specific advantages include:

- Granularity – permissions can be defined onto items as small as an object.

- Scale – group policies and roles allow attributes to be defined across multiple users, objects and buckets.

- Delegation – permissions can be delegated out through roles, assigning access to actions as well as object policies.

- Multi-tenancy – permissions can be divided up within a single AWS account or can be federated or delegated to another AWS account or group of external users.

- Audit – policies can be applied to audit the access of users across an account.

- Mobility – both data and policy can be moved between AWS accounts, regions or even to external object store providers that fully support the S3 API.

Issues

The implementation of S3 Security isn’t without issues. A few that stand out as being problems include:

- Complexity – for users new to AWS, the idea of security rules through code could prove a little challenging, however anyone experienced with LDAP and AD will be used to the idea of using code to access credentials.

- Eventual Consistency – IAM like every other AWS feature is eventually consistent across locations. This means it is theoretically possible to expose data as new security rules are put in place (hence AWS’ best practice to assume default permission of no permissions).

- Scale Limits – there are some IAM limits in place; accounts are limited to 100 groups, 5000 users, 250 roles and users can only appear in 10 groups. This may prove an issue with some customers (especially those who don’t want to use temporary credentials to program around the problem).

Summary

The implementation of security features in the S3 API are mature and well structured, supporting complex application integrations. Object store vendors providing 100% S3 API compatibility need to provide an equivalent to IAM that programmatically operates in the same way as the calls within S3 do.

The implementation of security also provides object store vendors the opportunity to deliver value-add functionality that isn’t directly in AWS, for example by avoiding the issue of eventual consistency, building a more GUI friendly interface, implementing hierarchical grouping or extending the limits within IAM.

Further Reading

- Object Storage: Standardising on the S3 API

- 2016 – Object Storage and S3

- WEBINAR: Everything you need to know about the S3 Object Storage Service and S3 API Compatibility (Cloudian website, retrieved 7 March 2016)

- Amazon Simple Storage Service Developer Guide (AWS Website, retrieved 7 March 2016, PDF)

Comments are always welcome; please read our Comments Policy first. If you have any related links of interest, please feel free to add them as a comment for consideration.

Copyright (c) 2007-2020 – Post #6ED2 – Brookend Ltd, first published on https://www.architecting.it/blog, do not reproduce without permission.