In August 2023, HashiCorp, Inc. announced that all future releases of software developed by the company would be moved to the Business Source Licence. This move caused consternation in the industry, with a group of users forking Terraform and launching OpenTofu. Does this splinter group really pose any threat to the future of commercial Terraform, or is it merely a temporary distraction?

Background

HashiCorp develops open-source software solutions for enterprise infrastructure management. Its portfolio includes Vault, Boundary, Consul, Nomad, Waypoint, Vagrant and, of course, Terraform. Terraform delivers infrastructure as code and is essentially an automation tool for building out virtual infrastructure.

As this post by co-founder Mitchell Hashimoto explains, the concept came from the launch of CloudFormation by AWS and the desire to see a cloud-agnostic and open-source version of the features CloudFormation offered. Terraform took some years to become an overnight success, with mainstream adoption in 2017 and only reaching version 1.0 in 2021. On achieving that milestone, HashiCorp claimed Terraform had been downloaded over 100 million times.

Licensing

On 10 August 2023, HashiCorp issued a press release indicating that all future versions of HashiCorp software developed under the open-source Mozilla Public Licence v2.0 would be moved to a more restrictive Business Source Licence v1.1.

The move was designed to protect the source code of all the HashiCorp products from being used to further develop commercial solutions. End users can still access the source code, modify it and redistribute it for free, as long as the use cases are non-commercial or don’t compete with HashiCorp if they are commercial in nature.

Effectively, any company building competitive products on HashiCorp open-source software will no longer be able to use future releases, including any feature enhancements, bug fixes and security patches.

Terraform

The most significant objection to the licence changes has come from the Terraform community, sparking the launch of OpenTofu, a fork of the Terraform code, pre-licence change. OpenTofu has subsequently been adopted by the Linux Foundation. The reasons for the decision to fork can be found in the OpenTofu Manifesto. Some of the details given for the founding of OpenTofu are a little vague and exaggerated. End users will be unlikely to see any difference in their use of Terraform. The group most likely to be affected are businesses that have taken the free code and built products on top of it.

Services

The majority of HashiCorp’s revenue is derived from support and maintenance sales for its open-source software (around 75%). To a lesser extent, an increasing amount of revenue is now derived from cloud-based services in the form of HCP, the HashiCorp Cloud Platform. Only approximately 13% of income comes from licensing. As a result, we can see the impact that competing businesses would have on the HashiCorp business model.

A competing business (including the public cloud) could take any of HashiCorp’s solutions and deliver either an on-premises or cloud-based competitive platform. HashiCorp, as the primary contributor to the code development of Terraform, would be effectively subsidising other commercial enterprises.

Fiduciary Duty

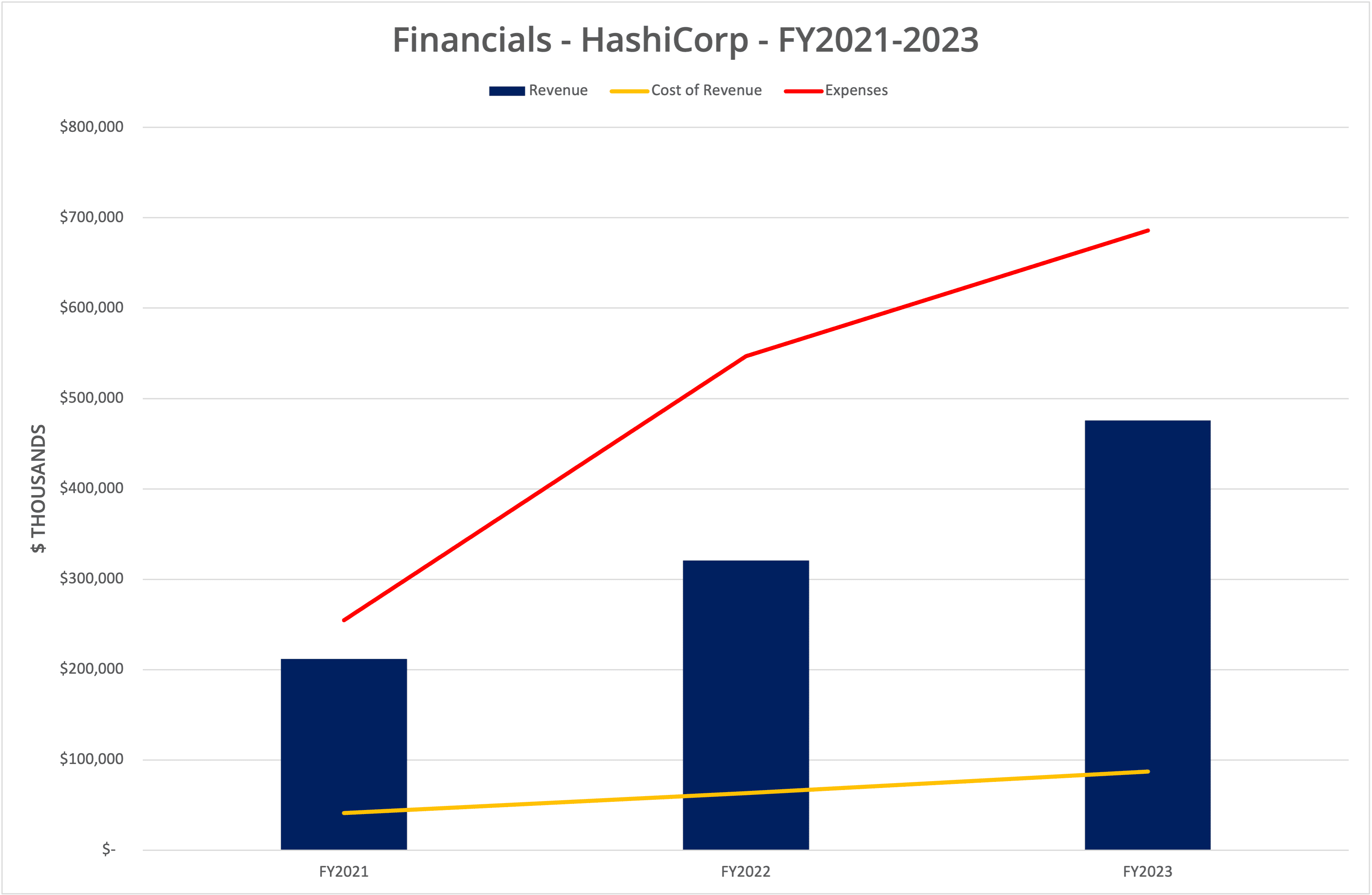

As a public entity, HashiCorp has a duty to grow the business, push towards profit and return value to shareholders. If we look at the data shown in Figure 2, HashiCorp has grown revenue significantly, as documented in the three years of published accounts. Unfortunately, expenses far outstrip income being brought in, although there is a slight trend towards that gap reducing.

The open-source model is a tricky balancing act for public businesses, especially in the public cloud era. There are countless examples of open-source software being appropriated to build new services. MongoDB and Elastic both changed the terms of their software licences in response to competing public cloud products. At the time, these changes generated much discussion but were soon forgotten. Meanwhile, MongoDB’s share price, for example, has risen from $65 on the day of the licence change announcement in October 2018 to $364 at the time of writing, almost exactly five years later.

OpenTofu

Does OpenTofu have a chance of being successful? First, we should note that a fork is not a long-term clone, but a point-in-time copy of software that immediately diverges from the original. Even if the OpenTofu project tried to emulate new features and functionality to match those in Terraform, the implementations would be incomplete and potentially flawed unless the code was identical.

HashiCorp would be able to out-innovate OpenTofu and continue to throw resources into Terraform. More importantly, Terraform would still be seen as the gold standard against which businesses would want to operate.

There’s also the issue of divergence due to the desires of the OpenTofu developers. Those teams may have unique ideas for how OpenTofu should develop that specifically and possibly deliberately diverge from Terraform. If that happens, then Terraform and OpenTofu would be two separate platforms that are increasingly impossible to interchange.

The Architect’s View®

OpenTofu may have a future as a platform that is separate from Terraform, with a unique identity and individual set of features. But just like HashiCorp, if the developers behind OpenTofu can’t make a profit from the software, then the project will quickly die off. I expect that if we look back in five years’ time, the fork will be a non-issue, and HashiCorp will still be in business.

What does yet another vendor change of licence mean for the wider industry? We can’t see much changing in the future. Start-ups will continue to use permissive licensing unless and until the risk of code appropriation raises its head. Perhaps we should all accept that free and open-source software will always come with some kind of future caveat that means “free forever” no longer exists. After all, if a commercial software vendor changed the terms of licensing, we’d all probably accept it or move on elsewhere.

Copyright (c) 2007-2023 – Post #234a – Brookend Limited, first published on https://www.architecting.it/blog, do not reproduce without permission.